How do life forms emerge?

I think it’s the biggest question anyone has ever answered. Charles Darwin, one of the greatest thinkers of all times, answered it in his book The Origin of Species.

In the book’s preface, Darwin writes:

[. . .] it occurred to me, in 1837, that something might perhaps be made out on this question [of how species originate?] by patiently accumulating and reflecting on all sorts of facts which could possibly have any bearing of it. After five years’ work I allowed myself to speculate on the subject [. . .]

Hidden in these lines is a clue to Darwin’s superhuman thinking ability. Can you imagine gathering ‘all sorts of facts’ for 5 years, all the while keeping yourself from speculating on it?

The idea of evolution is far from obvious. No wonder that Darwin had to show extraordinary patience to come up with it.

The problems you and I are trying to solve, fortunately or unfortunately, are nowhere as big as Darwin’s. So we can probably succeed with much less patience.

Why are we impatient?

Impatience is in our nature. Our brains have an inherent tendency to jump to conclusions.

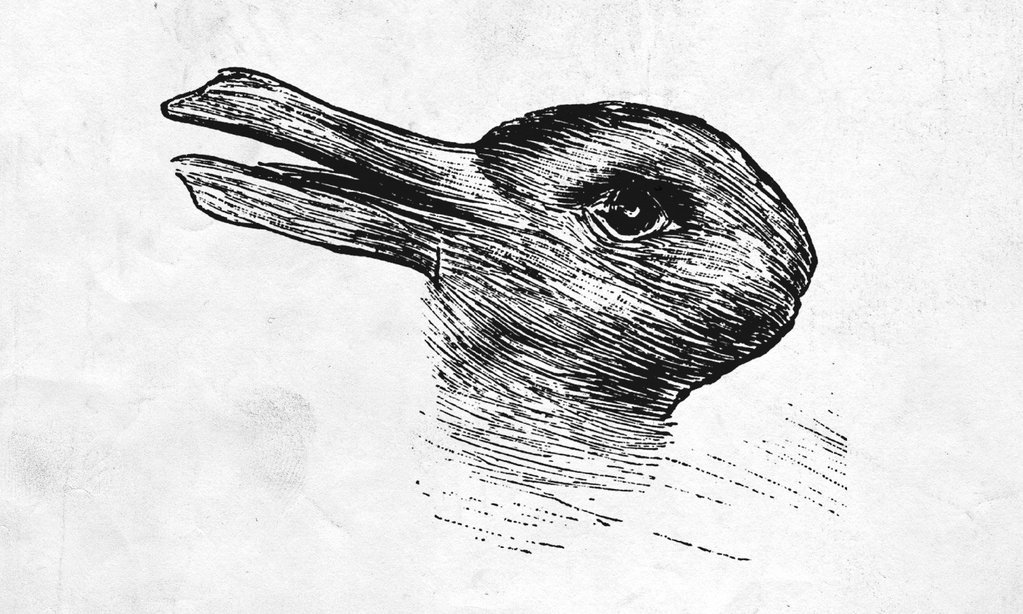

See the picture below. You would immediately see either a duck or a rabbit – but not both. Presented with a problem, the brain tries to come up with a solution as soon as possible and then falls back to resting.

Solving tough problems requires careful analysis. Which requires patience. Which is hard to practice if you want ‘instant results.’ Today’s society also prefers action much more than analysis.

All of this motivates us to make haste.

Consequences of impatience in problem solving

Haste causes many blunders.

In haste, we may misidentify a problem.

I was once mentoring a novice Javascript programmer. When he had learned the basics, to take him to the next level, I suggested him to read a book on JS.

After a couple of weeks I asked him, “So, did you read that book?” He said he begun, but had only read the first two chapters. Another couple of weeks went by but he still hadn’t finished the book.

I thought that maybe reading wasn’t his learning style. So I asked him to enroll in an online JS course. He had difficulty finishing it too.

Then I tried giving him some ‘hand-on’ exercises but they didn’t bring much results either. At this point, I didn’t know what was going on.

Then one day, while casually chatting, I asked him, “So what are your plans up next?” He said, “Now I have learned JS very well, so probably I should learn other languages.”

I was trying to solve a problem (of mode of learning) which wasn’t even there!

Another blunder hasty solutions lead to are second order problems.

The famous story where the government, in an attempt to eradicate rats, announced a reward for every rat, ended up with more rats because people started breeding rats for the reward — is a great example of how hasty solutions can make matters worse.

How Lincoln prepared his speeches?

Abraham Lincoln said, “If I had eight hours to chop down a tree, I’d spend six sharpening my axe.”

Lincoln made some of the best speeches in history. How did he prepare them?

He followed his own advice Some leaders employ specialists to write speeches for them. Some prefer to be spontaneous and never prepare a speech in advance.

But not Lincoln, no.

Lincoln used to begin preparing his speeches days, sometimes weeks before it was due. He wrote the drafts on slips which he carried around in his hat. Whenever he would have a few minutes to spare, he would take out the slip and edit the draft. Lincoln called this process ‘giving a lick,’ as in “I shall have to give it another lick before I am satisfied.”

Learning patience

If you want to come up with innovative ideas, you must learn to be patient. Carry around the solutions in your hat (so to say) and give them a lick every now and then. The classical advice ‘sleep on it’ is important for creative problem solving.

Do you want to begin right away? Here are a few exercises:

- Once you have a couple of ideas on how to solve a problem, strike them off. Pretend that for some reason, they are off the table. You cannot implement any of those. Think of new ideas. Repeat as many times as you can.

- Practice deep listening in conversations and write essays about the problems you want to solve. You will begin realizing that there is more to a problem than what immediately meets the eye. When you begin seeing those nuances, you naturally stop jumping to conclusions.

- Teach yourself patience more broadly. Try doing a slow but focused activity. As an example, I gave myself the task of wrapping my phone’s charging cable with a thin thread, which not only made it more robust, also gave me an opportunity to learn patience and focus.

Want to be 10x more innovative? Subscribe to our newsletter:

Cover Photo by Andre Hunter on Unsplash